By Eniko Takacsy on January 9, 2018

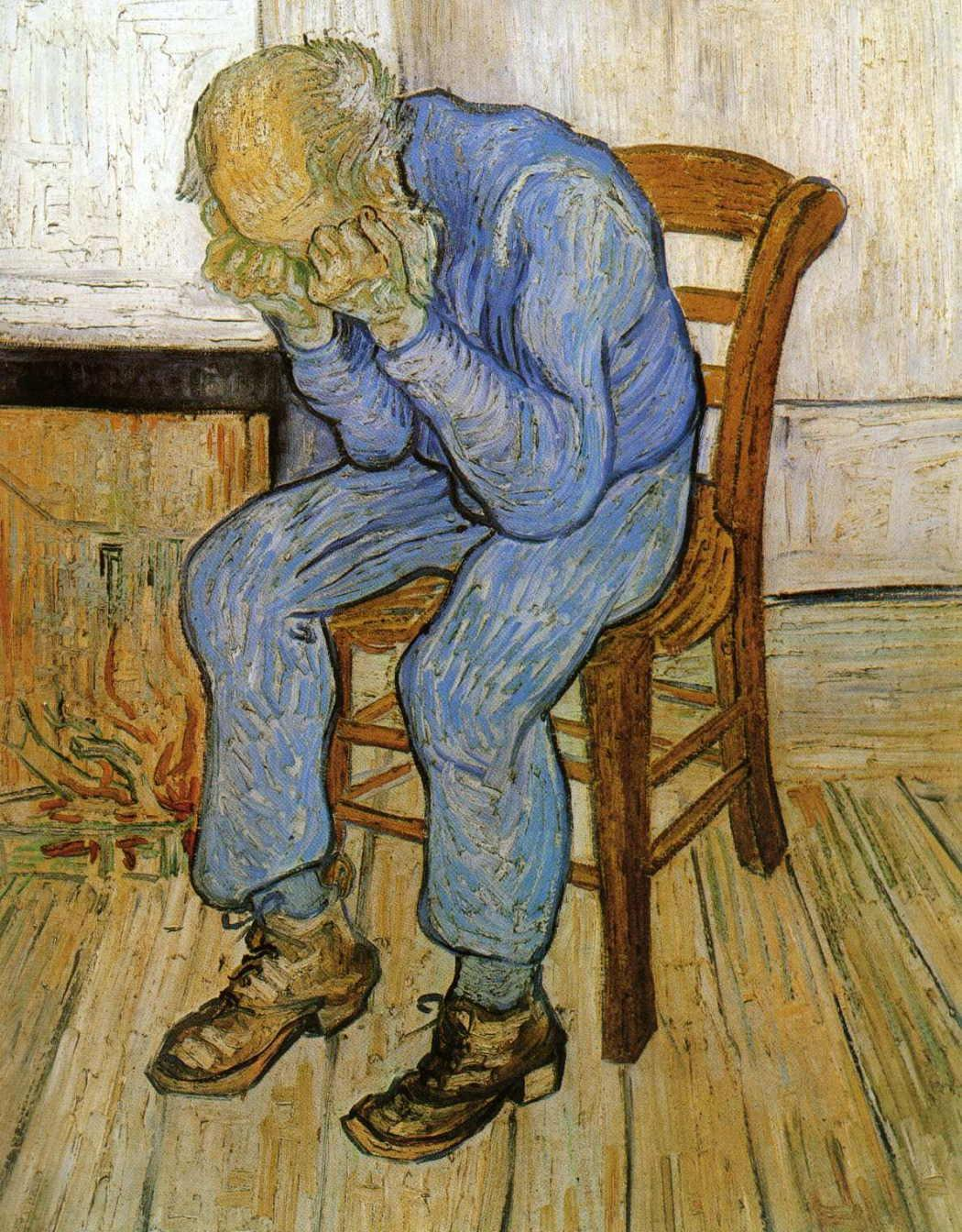

Loss shakes every one of us, irrespective of the myriad forms it may take, ranging from losing more abstract things, like a dream or our identity, to concrete ones like the person we loved the most. It is common in every loss that it always involves separation from an “object”, whether it is internal or external. The intensity of mourning varies depending on the amount of energy we had invested into the relationship with the “object” prior to the irreversible fracture.

Freud contended in his work Mourning and Melancholia that in the case of conscious object-loss, our ego, by means of its function to distinguish between internal and external reality—reality testing—, verifies the loss of the object, then commands to have all libido removed from it. However, this task cannot be easily accomplished due to the resultant resistance to painful libidinal detachment, which is a legitimate reaction to loss. Even when a substitute for the lost object has already been recognised, it still takes a considerable amount of time and energy for the ego to eventually break free from its relating inhibitions. Freud argued that in the example of unconscious object-loss, the melancholic person is not fully aware of what has been lost, however, his ego is still immersed in the response to loss. The unconscious dynamics of this process manifests itself in the symptom of severe delusional self-reproaches.

In melancholia, to which we generally refer today as depression—although, to be precise, what Freud was writing about would probably match one specific form of major depressive disorders—the underlying conflict can be attributed to the ambivalent feelings of love and hate in connection with the lost object. Strong negative feelings of hostility, anger and guilt are banished from consciousness and turned against the self, blurring the past that reveals itself in the presence of maladaptive defence mechanisms against normal grief, which, as a consequence, leads to a complicated grief process: delayed mourning.

Loss often triggers so much pain in us that we feel it is unbearable to hold. Yet no matter how hard we try to avoid or suppress it for a long time, consciously or unconsciously, it is necessary to work through it in order to transform depression into grief, and to enhance healing. Completing our grief work does not mean that we betray our loyalty to our lost “object”. It does not mean denying our memories either. Rather, it means reconciliation, which can result in a more peaceful, more mature and more transparent internal relationship with it.